Leadership, Culture, and Organizational Health: What’s Your Cat Hair?

Nearly all mammals play. Scientists believe that play has important evolutionary value for socialization, cooperation, and the development of healthy brains. In a famous experiment involving rat pups, neuroscientist Dr. Jaak Panksepp observed the young pups at play for many days straight, quantifying the frequency of their interactions. In lab settings, as in their natural habitats, rat pups play a great deal. He then introduced what he termed a “minimal fear stimulus” into the environment: a single cat hair. He left the cat hair in their cage for 24 hours, and then removed it. What happened?

Nearly all mammals play. Scientists believe that play has important evolutionary value for socialization, cooperation, and the development of healthy brains. In a famous experiment involving rat pups, neuroscientist Dr. Jaak Panksepp observed the young pups at play for many days straight, quantifying the frequency of their interactions. In lab settings, as in their natural habitats, rat pups play a great deal. He then introduced what he termed a “minimal fear stimulus” into the environment: a single cat hair. He left the cat hair in their cage for 24 hours, and then removed it. What happened?

The impact on the rat pups’ play was dramatic, not only for those 24 hours, but also for the foreseeable future. As summarized by Dr. Glenn Saxe et al (see Trauma Systems for Children and Teens, 2nd Edition):

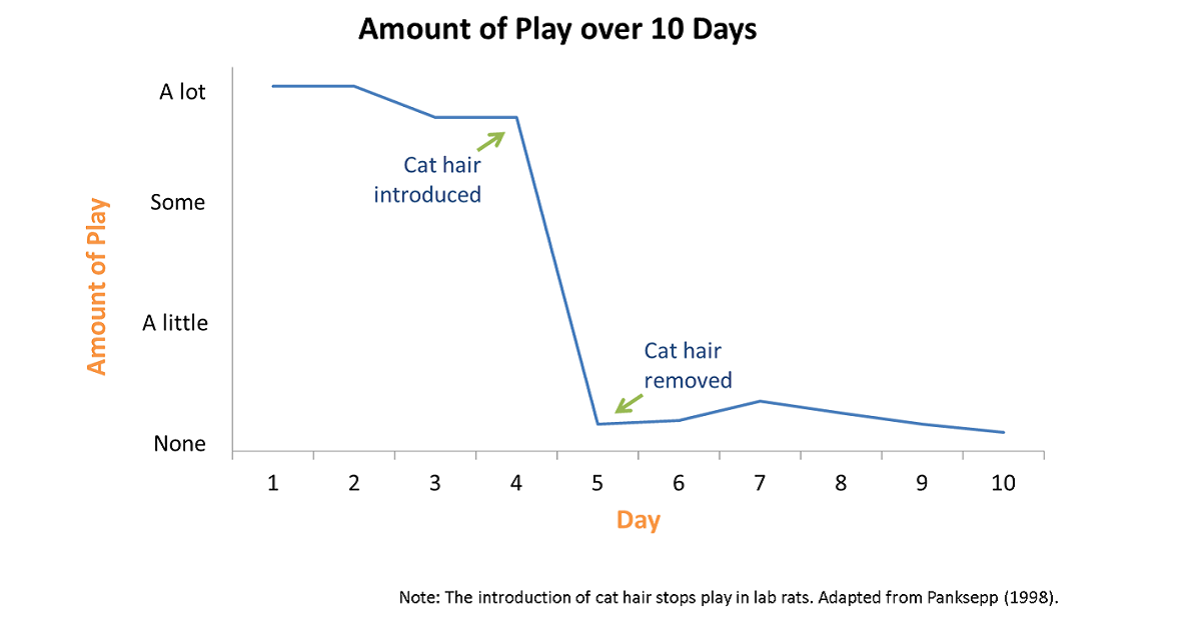

It’s important to know that these experiments are conducted with lab rats: They have never actually seen a cat. The figure below is adapted from Panksepp’s experiment and shows what happens. The y-axis shows the amount of play. The x-axis shows day. As you can see, the young rats are happily playing for four days. On the day the cat hair is introduced, play stops completely. Even after the cat hair is removed, play never returns to anywhere near the level it was before the hair was introduced.

For Panksepp, the most startling finding was the long-term effect of the stimulus. The introduction of a single cat hair into that safe container where the rats freely chose to play transforms it into a worrisome place where the potential threat entirely shut down creative, expressive actions and interactive group processes. Play is gone, forever.

Why does this matter? Because if they are not careful, leaders may inadvertently drop cat hairs into the work environment that can have major effects on performance.

Is this too much of a stretch? We’re humans, after all, not rat pups. We operate in social environments far more complex than lab cages. And thankfully, we appear to have developed more advanced means for relieving stress in many instances. Yet recent brain science indicates that humans possess an equally strong need for safety and security as other mammals and are similarly wired to respond to threats. What happens when a threat, even a seemingly tiny one, is introduced into our social environment? Can a single, subtle cue, a hint of danger, a whiff of menace, throw a switch that affects our highly attuned systems?

Yes it can, according to recent research findings. For example, multiple studies indicate that rudeness in the workplace, even mild rudeness, can have significant impacts on performance. In one simulation study published in 2015 in the American Academy of Pediatrics, researchers looked at the effects on a hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit staff when a visiting senior doctor made a rude or derogatory comment about the teams’ work. (An example: “Teams like the ones I have seen here wouldn’t last a week in my department.”) Following the comment, the teams performed significantly worse in simulated patient emergencies. Their teamwork deteriorated as well. They communicated less effectively and were less responsive in helping one another.

What’s going on? It appears that even mild rudeness kicks into gear our highly developed threat detection systems. In an instant, we shift to scanning the environment to see if further threats or other dangers are on the way. This mental switch drains away the higher order cognitive functioning needed to perform complex tasks well.

Tolerating rudeness and boorish behavior in our organizations is a cat hair. There are many others. Fear of failure is a cat hair. I have written about the importance of how leaders handle failure here and here. Leader behaviors, policies and practices can either create the cat hair of blame, finger pointing and risk aversion, or conversely, a rich, playful learning environment in which innovation thrives and creates a sustainable advantage.

Ethical violations are cat hairs. Wells Fargo is the latest of too many organizations whose leaders lost sight of their moral compass and allowed unethical practices to shape a culture of wrongdoing.

Discriminatory behavior is a cat hair. Lack of inclusion is a cat hair. Recent highly publicized examples of women’s voices being silenced or denigrated in Congress and in boardrooms have brought these cat hairs to the forefront. Research demonstrates that diverse teams perform better. Yet leaders whose discriminatory and exclusive behaviors weaken and diminish their organizations often remain in place too long.

It appears that many cat hairs had been dropped into Uber’s workplace before investors finally organized to oust CEO Travis Kalanick. They understood that even a company with massive brand recognition, great technology, and a valuation of $68B is imperiled when leaders create a toxic culture. Following Kalanick’s announcement, The New York Times summarized the situation:

The move caps months of questions over the leadership of Uber, which has become a prime example of Silicon Valley start-up culture gone awry. The company has been exposed this year as having a workplace culture that included sexual harassment and discrimination, and it has pushed the envelope in dealing with law enforcement and even partners. That tone was set by Mr. Kalanick, who has aggressively turned the company into the world’s dominant ride-hailing service and upended the transportation industry around the globe.

Notably, it was not angry employees or irate consumers who forced a change in leadership, but five of Uber’s major investors. The message is clear: Leadership matters to business success. Increasingly, leadership quality and cultural health add to or detract significantly from a company’s value. (Further proof that Peter Drucker had it right: “Culture eats strategy for lunch.”)

Fortunately, we aren’t rat pups. We can change our environments. We can recover. But sometimes it takes extraordinarily strong actions to signal cultural change. And cynicism can persist and drag down engagement, commitment, and productivity well after the cat hair has been swept away.

Changing leadership at the top, as Uber is doing, may be essential, but changing the culture is never easy. All too often it plays like a line from The Who: meet the new boss, same as the old boss. MDA Leadership has helped organizations do this thoughtfully and methodically, working with boards and executive teams to define requirements that go well beyond the skills needed to drive quarterly profitability. The profile for a successful CEO and leadership team must include the ability to shape healthy, collaborative, prosperous cultures. Smart organizations also use assessment (validated cognitive tests, personality instruments, and level-appropriate simulations) to obtain deep insights not only into a prospective leader’s business acumen, but also her motives, values, potential personality derailers, and cultural fit.

The right leader at the top sending the right signals can make a big difference. But it takes more than a new and improved chief. Our best client organizations clarify what effective leadership looks like at all levels to create well-run, high performing cultures. That means investing in defining a behaviorally rich, “built here,” aspirational model of leadership effectiveness. Aspirational does not mean pie in the sky. Rather, it means that we have defined proven leadership behaviors tied to the reality of how we operate when we are acting as “our best selves.” The best models go beyond the “hard” competencies of business acumen, strategic thinking, and execution to areas such as trust, respect, fairness, empowerment, engagement and inclusivity.

The hard work of reshaping a culture continues when those leadership expectations are integrated into all talent systems: selection, onboarding, performance management, training, career development, high potential assessment, and promotion.

It’s a wise and sobering exercise for organizational leaders to ask, “What is your cat hair?” Great leaders recognize these toxic elements and have the courage to remove them. They invest in the right people, processes and practices to create collaborative environments where engaged employees make great things happen.

About the Author

Jim Laughlin serves as Senior Vice President, Leadership Development for MDA Leadership Consulting and is based in the Boston area. For more than 20 years, Jim has designed and implemented learning and leadership development systems for companies worldwide. He is also a sought-after executive coach with expertise in organizational communications, change and transitions. More About Jim